Last day I told you about photographic methods that use organic elements such as leaves and flowers to create photographs, and today I am going to talk about this relationship within pictorial art.

Artists have many ways to make their art contribute to a more responsible use of natural resources, reduce its environmental impact (especially in terms of waste, as we also saw in analogue photography) and develop in contact with nature.

Art stands as a powerful tool for exploring and understanding the natural world around us. Through creativity, artists have the ability to capture the essence of nature, revealing its beauty and complexity in thought-provoking ways. By connecting with the elements of the environment, art not only provides us with a visual representation, but also inspires us to observe and appreciate the details we often overlook. In this article, we will explore how art can enrich our understanding of the natural world, encouraging a mindful practice that invites us to care for and value our environment.

ART, NATURE AND SCIENCE

The relationship between art and nature is unquestionable, both as a source of resources and inspiration. We see this both in the traditional creation of pigments for oil or watercolour paintings, as well as in artistic interventions that take place in the natural environment.

From prehistoric cave paintings to the contemporary world with artists such as David Popa, who creates impressive “ephemeral frescoes in the earth” with natural pigments (charcoal, chalk and water), humans have connected with the earth through art.

In this article I unravel the differences between botanical art and artistic or decorative flower painting, review its historical evolution and, at the end of it all, I propose you to create your own illustrated herbarium, providing you with a downloadable template as a reference guide, and a video on how to illustrate in watercolour by my friend the artist Alicia Gomar.

WHAT IS BOTANICAL ART?

If we talk about botanical art, the first thing we need to know is what it is and what differentiates it from other floral paintings.

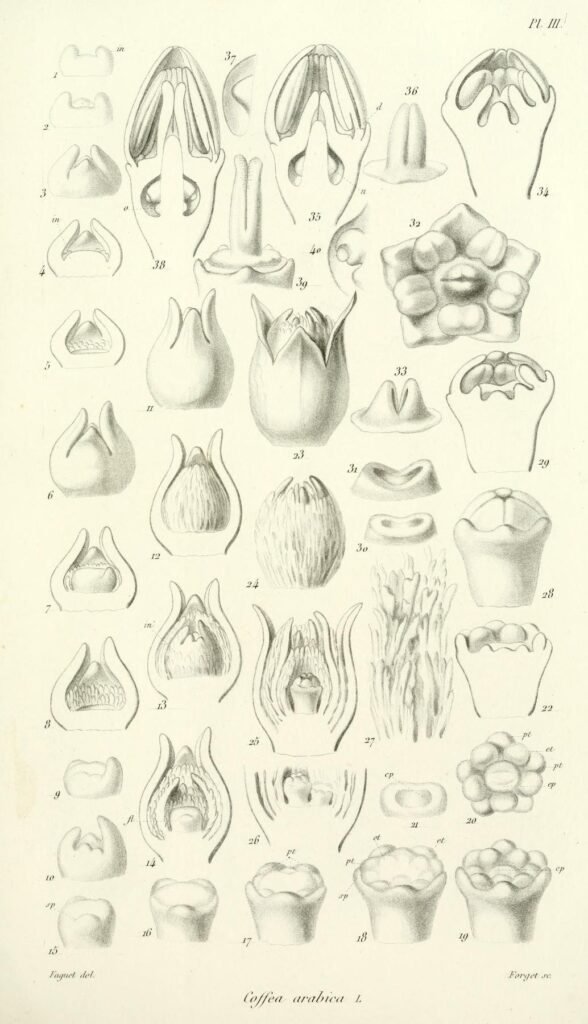

The answer lies in the precision and rigour of the work, its purpose and where it will be published. Alice Tangerini, an illustrator in the botany department of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) says that “one of the ways that somebody distinguished botanical art from fine art is that botanical art had to be recognized at least to genus, if not to species [of the plant]” (source). Alice alludes here to the precision in the drawing that allows the correct identification of the plant.

Botanical illustrations accompanying academic works have a clear scientific purpose and should follow certain conventions so that they can be easily interpreted by botanists. It may also accompany scientific annotations in monographs on taxonomic groups and in journal articles describing newly discovered plant species. If the illustration is in a gardening magazine, it will be less detailed.

Judith Magee, curator of rare books at the Natural History Museum in London, comments in this video that the purpose of botanical art is “to assist scientists in their work of identifying, describing, classifying and naming species” (2011). Botanical art, however, has not always followed a single trend. Judith explains how the dominant tendency to present in a single illustration the various parts of the plant useful for its identification was countered by another tendency among naturalists who preferred to see nature as a whole and to paint nature as they saw it in the natural world.

In botanical art, therefore, the relationship between nature, science and art is very close. “We [artists] bring the botanists’ words to life”, Lucy Smith, botanical artist at Kew Gardens in London, tells National Geographic. Its scientific value and functionality define it, as opposed to a freer floral art, which can allow itself artistic liberties for the sake of aesthetic or decorative function.

A BIT OF HISTORY

To better understand botanical art today, we must first look back and see where it comes from.

While there are antecedents in the Renaissance, such as the illustrations of Leonhart Fuchs (from a medicinal and healing properties point of view) or the botanical drawings of Leonardo da Vinci (who is already interested in the structure of plants per se) or Albrecht Dürer, the “golden age” of botanical art is considered to be the 18th century, thanks to the explorations and discoveries of that time.

Dr. James Compton explains in his book Plants, that it was the “age of reason” in the 17th and 18th centuries that introduced a new spirit of scientific enquiry and an interest in plant collecting that led wealthy patrons to hire artists to record their plant treasures.

In the 17th century botany established itself as an autonomous scientific discipline, independent of medicine, and floras and florilegios appeared. With the constant discovery of new species, the need arose to establish order: to identify and classify them systematically. It was Carl von Linnaeus who, in 1753, introduced a binomial system according to his taxonomic theory: each plant is given two Latin names indicating its genus and species. Further, other conventions were added, and today the International Code of Nomenclature is the current standard.

At this time, artists travelled on scientific explorations, documenting and recording the flora of the places they discovered. It is worth noting that women played a very important role in the development of botanical art at this time, although they have generally not received as much recognition as their male counterparts. The Oak Spring Garden Foundation talks about them in this Google Arts & Culture article.

Does photography pose a risk to illustration?

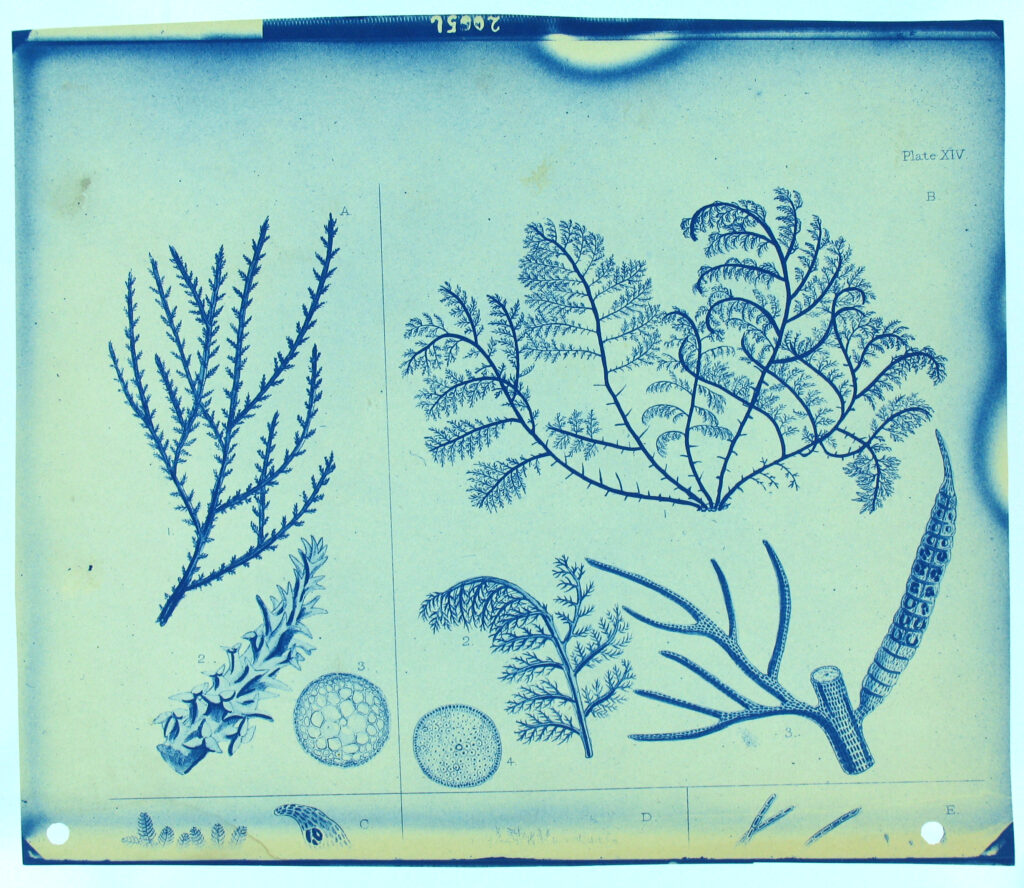

In the 19th century, the leading role was played by photographers rather than illustrators. The experiments that began to be developed at that time with photosensitive materials allowed a new approach to image capture. The invention of the daguerreotype and photograms, among others, made it possible to reproduce images of plants as faithfully as never before.

The question of whether photography could replace illustration in scientific work has been raised on numerous occasions. Michelle Meyer, a botanical artist specialising in orchids and vice-president of the American Society of Botanical Artists, said: “you can never get all the information about a plant in a photograph, because something’s always out of focus or in a shadow, [whereas] in a botanical [illustration] you can bring everything into perfect focus” (source). However, with the advance of technology and the possibility of editing images in post-production, it is now possible to get a 100% focused image from numerous shots.

In the book Manual de ilustración científica by the publishing house Geoplaneta (2022) it is written on this subject: “nothing could be further from the truth […] in the illustration of an organism, reference is not made to a specific specimen, but to an ideal representative of all the individuals of the same species” and, certainly, this is something that differentiates it from photography.

Rather than opposing them, we should see that they go hand in hand and can be mutually nourishing. Technological advances (such as X-rays) have made it possible to see previously unimaginable details that have further enriched artistic production.

PAINTING FROM LIFE OR FROM A HERBARIUM

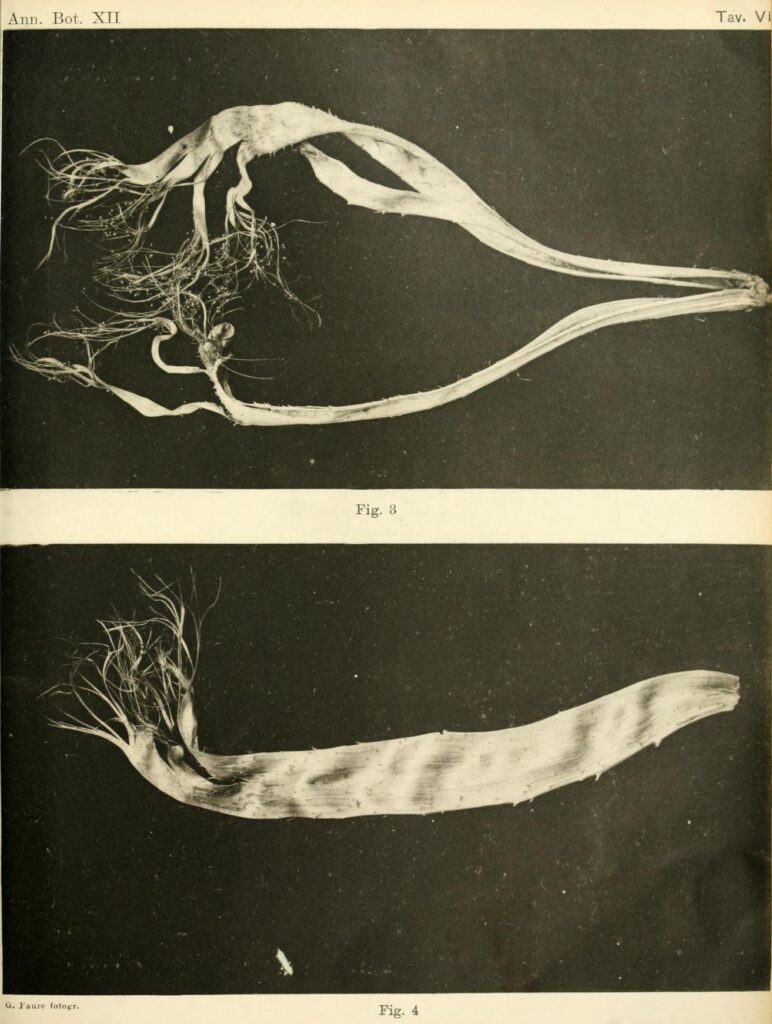

When painting a plant, there are many sources of inspiration. Botanical artists draw and paint both living plants in their natural habitat, as well as those grown in greenhouses or collected and painted in their studio. “In the case of scientific illustrations, the subject is usually a herbarium specimen, a plant collected and dry-pressed between sheets of paper in a centuries-old process that preserves the specimen, but leaves it flat and relatively colourless” (source).

Each option has its own advantages and disadvantages. For example, painting au naturel involves the difficulty of adapting to the climatic conditions of the moment and the discomfort of the territory. Arranging the materials comfortably is complex, as is adapting to changes in light as time goes by. One option to solve this problem is not to carry out all the work on site, but to finish it in the studio by taking notes and photographs. At the end of the article, in the template I have prepared for you, I have taken this factor into account.

On the other hand, painting from a herbarium specimen entails other difficulties. Dry pressing changes the qualities of the plant, so that many botanical illustrators “reconstitute parts of the dried plant by heating them to boiling point for a short time in a special solution of water, alcohol and a wetting agent” (idem), to bring them back to life so that they can be reproduced.

In botanical illustrations accompanying scientific publications, we can often also see detailed views that come from a dissected view of the plant under the microscope.

Today, to become a professional botanical artist, there are opportunities for formal and certified training. But there are also other ways of approaching the illustration of the natural world from an aesthetic point of view, encouraging the use of new techniques and synergies with other artistic fields outside the scientific field.

YOUR ILLUSTRATED HERBARIUM

According to the RAE (Real Academia Española), a herbarium in botany is a collection of dried and classified plants, used as material for the study of botany. As we have seen, botanical artists use them as models for their illustrations, breathing life into them by soaking or boiling them in water.

After this overview of the definition and history of botanical art, let’s open up our horizons a little: I propose you to create your own illustrated herbarium. Get to know the environment around you better through drawing, photography and collecting (when possible) specimens.

DOWNLOADABLE TEMPLATES

If you do not know what data to include in your herbarium or how to distribute the information, you can download this template:

In the template you will find recommendations and ideas for the design and layout of your illustrated sketchbook. If you use single sheets of paper, the “numbering” section will allow you to arrange them later and bind them (e.g. with Japanese stitching).

EXPLANATORY VIDEO WITH ALICIA GOMAR

Don’t you know how to draw and paint your botanical illustration? The artist Alicia Gomar explains it to you step by step in this video.

Here you will learn how to make the illustration, from drawing to colouring in watercolour, and how to give plasticity to your sketchbook. It includes information on inking and freehand writing or lettering.

You can activate the English subtitles on Youtube as the original audio is in Spanish.

By creating this herbarium you will learn more about your environment, you will discover curiosities about plants that you had never noticed before, and you will look at nature with the calm that painting requires. If you have any questions about how to create your notebook or any ideas based on your own experience in this field, don’t hesitate to write a comment!

Now it’s your turn: share your results on social media. Tag me on Instagram (@albacid_) and I’ll be happy to share your botanical illustration!