About the project

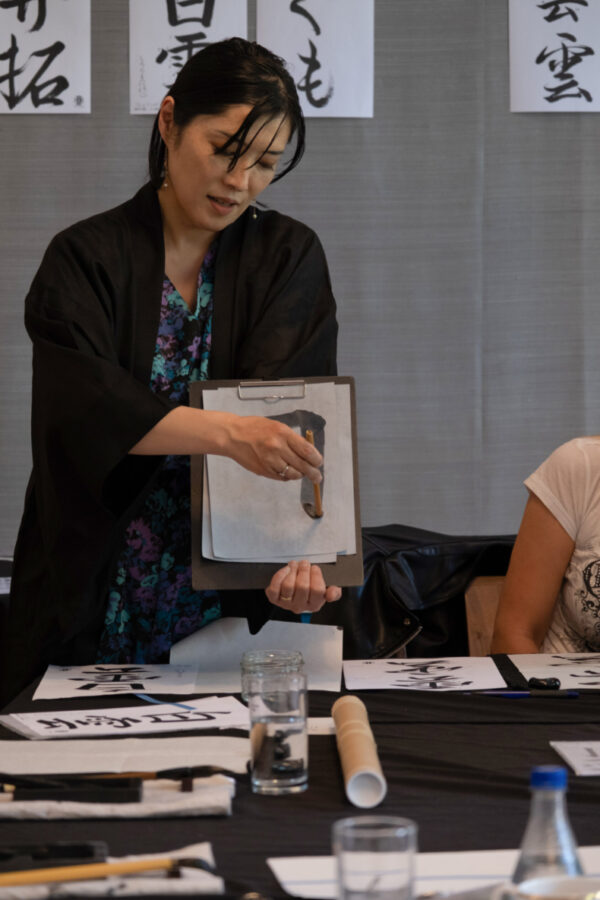

Introduction to Rie Takeda’s Body Art project

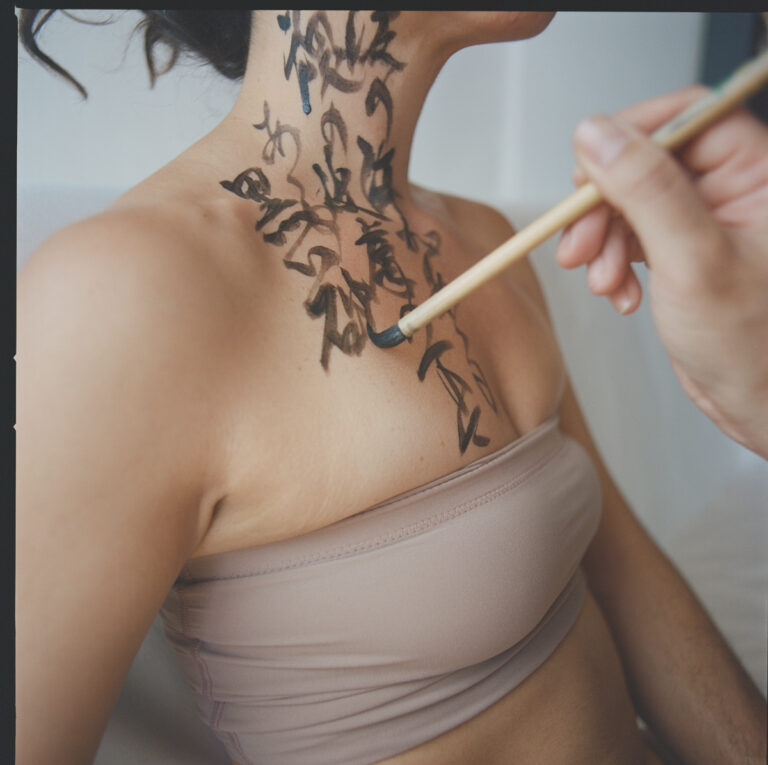

“It is a very intimate project; it is not commercial as it may sound. It’s about the real way to intervene the calligraphy and design poetry. The meaning becomes alive on the human skin. The mindfulness factor is essential, because it is a very healing process for both sides: the model and me. It is not a make-up, you really ‘wear’ the meaning of what you want to share; it is a very fascinating process”.

This is how Rie Takeda, a Japanese artist and calligrapher based in Europe, defines her Body Art project. The artist uses Japanese calligraphy to write on a person’s skin a poem that brings to life a personal experience or process.

For me, this project is also a way of contributing to the preservation of traditional and historical art forms, such as shodo and analogue photography. This fusion gives rise to a contemporary take on tradition.

Creative process:

After several exchanges, Rie composed the poem. Then we developed the working session together with the director Karin Berndl. Rie calligraphed the poem on my body, turning it into a message that goes beyond the aesthetic appearance, in calm and silence.

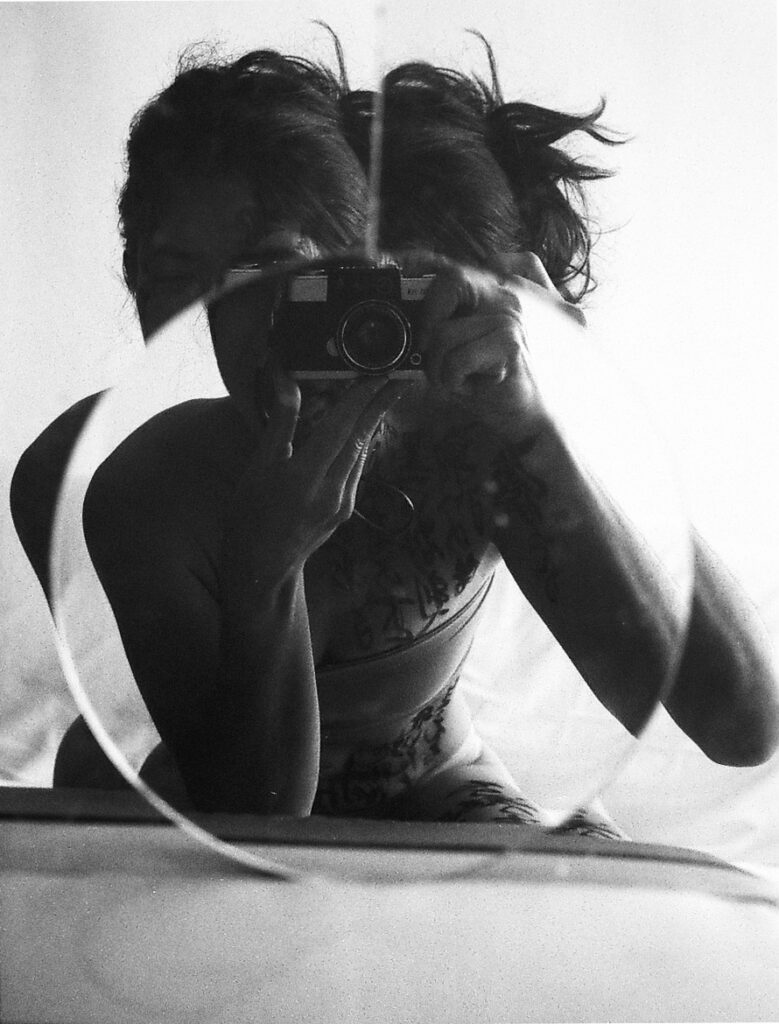

Part of the work we developed had to do with gazes and reflections. My present self and my self on the other side of the mirror. For that reason, the analogue photographs I took are self-portraits constructed through a display of mirrors. During the process, Karin has subtly documented the work.

Reflections

Through my eyes

Analog self-portraits. Inspired by Alice through the the looking-glass, I created these photographs through an arrangement of mirrors. The different angles of each reflection show a different picture, referring to the multiple layers that make us up: complementary and versatile.

The final image of myself is created through several lenses: the camera optics, the mirror, my eye, the eye of the viewer (your eye).

*Photographs taken with an Olympus-Pen D3 (half-frame) from the 60’s, bought in a hidden shop in Tokyo, with film Professional Acros 100II.

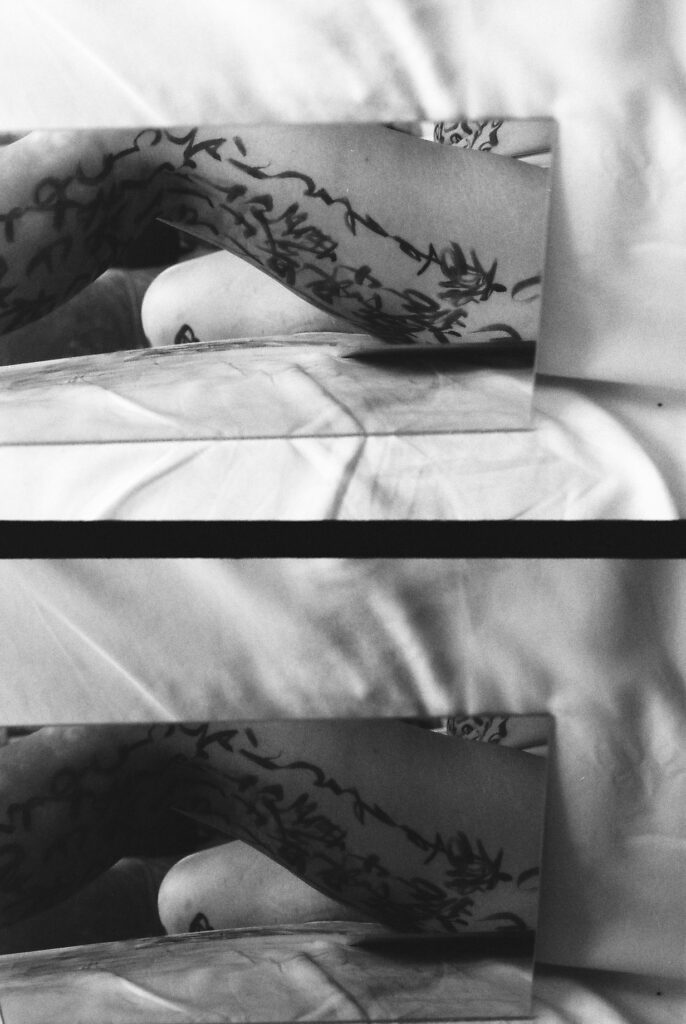

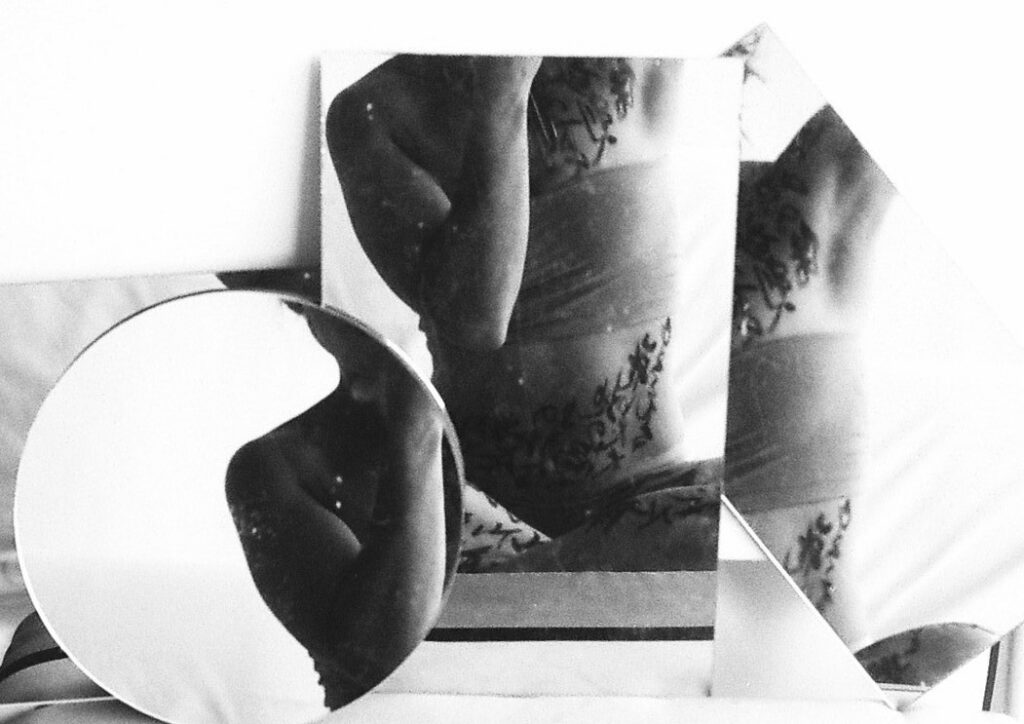

Plastic intervention

Subsequent work on the photograph on paper to recreate the Kintsugi or Kintsukuroi method that gives its name to this project.

KINTSUGI (Japanese: “golden joinery”)

Also called kin·tsu·ku·roi [kin-tsoo-koo-roi] A traditional Japanese technique of repairing ceramics with lacquer and a metal powder that is usually made from gold or silver. The centuries-old practice is often used to mend treasured objects by beautifying the cracks, which serve as a visual record of the object’s history (definition by britannica.com).

In this project, Kintsugi is the metaphor that gives meaning to everything.

Through Karin's eyes

© Photo, video and editing : director and photographer Karin Berndl

Interview with Rie Takeda

Want to know more about Rie? Here you have more details about her career, her experience as a teacher and her projects as an artist, explained by herself.

Could you briefly introduce yourself?

My name is Rie Takeda, born and gowned up in Japan. I am an artist, calligrapher and a shodo teacher. I have taught Japanese calligraphy for more than 25 years now, and with the mindfulness method since closer to 15 years. I work in Europe and Britain, and when I am back in Japan, I make projects and work with colleagues and children too.

How many years have you been living in Europe?

I’ve been living in Europe for more than 20 years! Initially, I was based in London, but since my daughter was born in Germany I tried to settle there more. I still go once per month to London to do workshops though.

Are you homesick for your country?

I don’t feel homesick but I do miss my family, friends, the food… but I go back every year to spend the whole summer there, about 6 weeks. I have an atelier at my parent’s house, so I like this balance: during summer in Japan, I can transform my sketches and ideas into realizations.

How did this going back and forth between Europe and Japan influence you and your work?

I think that through this ‘in and out’, ‘west and east’, I could see many different elements, analyse and compare them. Also, the island vs land mentality, and other differences such as religious factors, have affected and influenced my work.

I am very impressed by the variety of your art work and by your collaborations in different fields such as fashion or video games. I believe that back in 2019 you were immersing yourself amongst the native Ainu population. How was this community-based art project?

That started as an individual and personal project with an old lady with the aim of helping me to introduce the meaning of Ainu arts (artforms and patterns that are very geometrically). Unfortunately, before the project went further and became deeper, Covid arrived, so we had to pause it. I may visit her this summer, but she is very busy, so is not fixed yet.

Do you believe that art can help preserve cultural identity in an increasingly globalised world of mixed cultures?

I really believe that shodo helps to preserve culture and identity. It can also help to be more aware of the individual and inner value of each as a result. Through this practice, you learn, question, accept and become aware of your heritage, so it can help your well-being, your self-esteem…

As the creator of Neo-Japonism style, how would you describe it in a few words?

In short, Neo-Japonism is the fusion of traditional calligraphy, Japanese design and poetry, with contemporary artistic forms. The two key essences in contemporary forms of this style are Japonism (the influence of Japanese art and design among Western European artists in the 19th century, especially artists from Paris and Vienna), and the Taisho period (from 1912 to 1926 – a time of curiosity and creation of a new combination of colours, designs and letters by hand).

You currently offer several online courses; is it easy to teach shodo online?

At the beginning, it wasn’t easy at all. It took me some time to bring the best quality to my online courses format because of the way I teach, pretty much based on the inner energy movement (the chi). But now, I am very pleased with the quality I can offer. I use 3 cameras, so the student can see the detail of the brush movement, and I often ask them to have a second camera too (or to change the angle), so that I can see the details of their work. Because of my teaching experience, which is quite diverse and long, I can quickly see the problem they are facing and help them.

Thanks to being online, have you reached people in faraway places?

Yes, I am very thankful because I have students from all around the glove at the moment, and they are calligraphing together. Before Covid, I only had a few long-distance learning students, but then it was a shift. I am surprised how even online there is this particular and intimate connection. It is a bit different from in person, but it works pretty well for me so far, and I think they are quite happy with what they are achieving too.

How is it to teach in Europe a traditional art from Japan? Is the cultural leap a hindrance?

It is a fascinating process because I teach and I learn at the same time. When I teach in Japan, certain elements are not questioned, they are natural and obvious. But in the West, you have to analyse and explain why it is so. Even why you should hold the brush like this or use that angle and not another. That was really refreshing and a good basis to develop my mindfulness process. Thus, the cultural leap became an advantage for both me as a teacher and learners.

Working with calligraphy as a form of meditation, it could be useful for those seeking to do personal work through art. Could you tell us about how are you helping people going through physical or mental suffering, and about your project working with therapists for developing a complementary treatment?

My students come from different backgrounds, age groups, places and professions. Each of them has different bodily tendencies and perhaps physical or mental traumas. Through the way we prepare the ink or our body for the lesson, we release this inner stress. The fascinating point in shodo is that you can see this process visually and instantly in front of you, on your paper. It exists a synchronisation between how you feel and the calligraphy, and this may help to raise awareness, and then to accept it and work on it. You can discover your self-tendencies and then see your progression from A to Z. That helps to get calmer very quickly, and when you have chronicle pain it easiest it up. This is why I work with professional therapists assisting them when they need to work with these therapeutical artworks. It is a nice healing process.

Thank you so much, Rie!

learn japanese calligraphy

Courses and a Shodo book by Rie

Looking forward to learn Japanese calligraphy? You can attend Rie shodo classes, available online or in London!

If you prefer to practice at home, you can also get Rie’s Shodo book, called Shodo: The practive of Mindfulness through the ancient art of Japanese calligraphy – available soon in Spanish and French!

The poem: KINTSUKUROI 金繕い Golden Trace

私の肌には、女たちが泣いたことのない涙の海がある。

魂の皮膚の下にある黒い砂利は、

戦いの傷を癒すため、その顔を表に出す。

傷跡は証であり、草が再び生える乾いた大地の渦のようなものだ。

金粉と樹脂は、壊れた自分の破片をゆっくりと繕う。

My skin holds the ocean of tears that women have never cried.

Black gravel under the skin of the soul

comes to the surface to heal battle wounds.

The scar is the trace, like the gyres of the dry earth where grass grows again.

Gold dust and resin mend the broken pieces of myself.

Introduction by Alba Cid

私の涙の海には、壊れた鏡がちらばっている。

目には見えない小さな破片、とがった大きな破片。

そんなかけらたちを 一つひとつ拾い始める。

見つけ出した破片は、水面と共に私の顔に反射する

パズルの様に並べてみても

合わせ目はきれいにはまらない。

傷口を癒すようにそっと優しく

破片の端を磨いていく。

指を切らぬよう、たまに深呼吸をして。

そして,全ての破片を地図のように

そっとつなぎ合わせていく

繋ぎ目は、波模様のようにもり上がる。

これは私の戦いの傷。

私はこの傷跡に柔らかな太陽を当てて

金粉を振りかけることにした。

金色のつなぎ目は、光を反射してよりひかる。

金の跡は私にいつも語りかける

私は色んな戦いをたくさんしてきた。

様々な箇所が壊れていた。

たくさん生き延びてきた。

今はあなたを誰よりも早く温めることができる。

何よりも折れにくく、壊れにくい

私は、川の流れのように

柔軟に変化することもできる。

この黄金の輝きは私の誇り、

美しい私の明り。

The sea of my tears is littered with broken mirrors.

Small pieces invisible to the eye,

large pieces with pointy angles.

I begin to pick up these bits one by one.

The pieces I find reflect in my face along with the surface of the water.

I put them together like a puzzle.

The pieces don’t fit into place properly.

Gently, gently, as if healing a wound

I polish the edges of the fragments.

I take a deep breath every once in a while, to avoid cutting my fingers

Then I join all the pieces together like a map.

The joinery is uneven and bumpy, like a wavy pattern.

This is my scar from the battles.

I let the soft sunshine on this scar

I decide to sprinkle it with gold dust.

The gold-colored joinery reflects the light and shines more brightly.

Gold scars always speak to me.

I have had many battles of all kinds.

Many parts have been broken.

and I have survived many.

Now I can warm you faster than anyone else.

I am above all unbreakable

I can also change – flexible

Like the flow of a river.

This golden glow is my pride,

My beautiful light.

Main text by Rie Takeda