INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION

Today we talk about the importance of archaeological research for future generations by travelling to a little-known but important area in ancient times: the Indus Valley.

A civilisation arose here contemporary to those of Mesopotamia and Egypt, and here we find one of the earliest examples of urban development. However, this civilisation is unfairly much less well known.

The work carried out by the archaeological research teams that study it, both at the sites and in the laboratory, is also little known.

That is why today we will take a journey that begins in Pakistan and ends in Barcelona, which will allow us to understand how the study of the past helps us to better understand the present. During this journey, we will also raise questions of ethics and sustainability in the conservation of cultural heritage.

We will do all this with Carolina Jiménez, research assistant in the ModAgrO project. Will you join us in the Indus Valley?

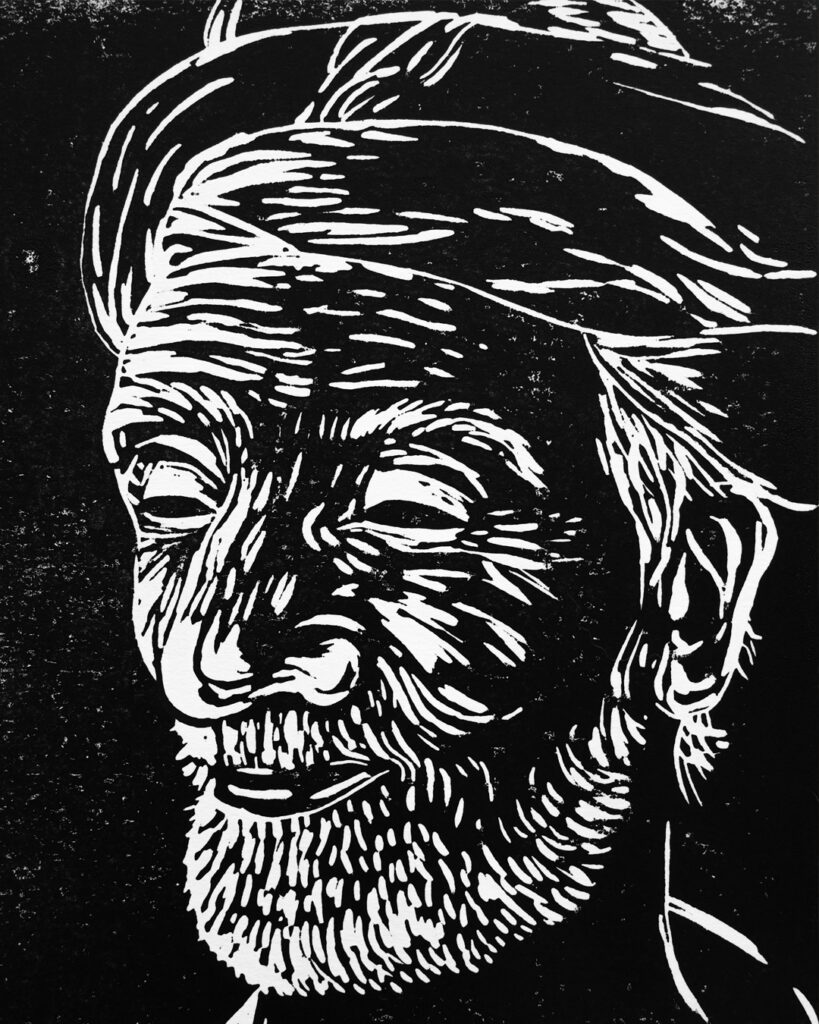

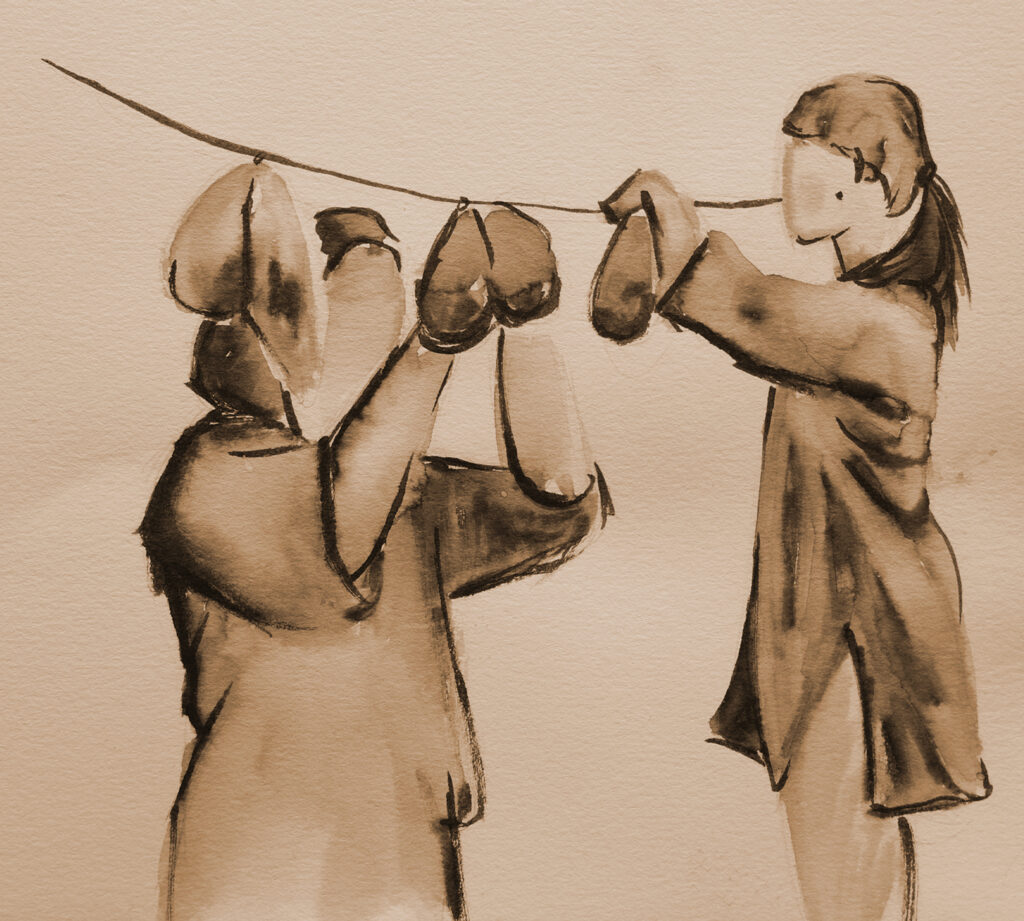

The graphic representations in this article are based on photographs provided by Carolina.

Carolina and the ModAgrO project

The ModAgrO project (MODELING THE AGRICULTURAL ORIGINS AND URBANISM IN SOUTH ASIA), is a collaboration between CASEs of the Universitat Pompeu Fabra and the Department of Archaeology of the Shah Abdul Latif University (SALU), and is part of JASPAR (Japan, Spain, Pakistan Archaeological Research Initiative).

The project collects and studies archaeological and palaeoenvironmental information from the Indus alluvial plain in northern Sindh, Pakistan, to address questions such as the origin of agriculture and its role in the emergence of the world’s first urban civilisations.

The sites being explored are in different ecological zones: the first was in the alluvial plain, the second almost on the border with the Tar desert, and the last – which is now being analysed – is in a mountainous area. This makes it possible to see if there are differences in agricultural dynamics due to climate and environment.

Within the project, Carolina is a Research Assistant, giving specific support both in research (archaeobotanical analysis) and management (logistics of travel, accommodation, etc.).

A day in the life of Carolina in Pakistan

What a day at work is like

It is 5 am and Carolina’s alarm clock rings in Pakistan. The working day starts early, as the sites are in very hot areas and the peak hours have to be avoided. Carolina gets up and has breakfast: eggs, fruit and chai tea. Tea is very important, she drinks at least 5-6 a day. Afterwards, she prepares the equipment, both personal (paddle, field notebook, headscarf, sun cream…) and collective (gear and water bottles).

The excavation starts around 6 am. While part of the group works on the site, Carolina takes care of the flotation work at home. This technique is used to recover carbonised plant remains (seeds and wood) by floating them by density in water: the carbonised materials, as they weigh less, float on the water, while the rest of the sediment remains at the bottom. Carolina decants it and recovers the remains, which must be dried before they can be stored and exported to Barcelona, where they will be analysed in the laboratory.

Between 12.30 and 14h, they take a lunch break in the shade of a tree, on a cloth, and then continue working until the sun sets around 17h.

Once the work at the site is over, work continues at home, making an inventory of each of the pieces and elements that have come out of the excavation that day. Everything is labelled and documented in an excel file. Graphic documentation (measurements, drawings, photographs, etc.) is also very important, as archaeology is destructive and it must be recorded what the element looked like before it was altered

Afterwards, Carolina has between 1 and 2 hours of free time. She takes advantage of this time to take a shower (sometimes she has to boil water on the stove first and mix it with cold water, as there is no hot water), wash clothes, hang them out, read, call her family… Finally, dinner around 7.30 pm, usually pulses, lots of vegetables and always white rice to go with it, as well as chapati bread -usually wheat bread (like Indian pita)-, and some days meat or fish and yoghurt. Sometimes after dinner she stays to chat with her work colleagues, although she usually goes to sleep, as she has to get up early again the next day, and at the end of the campaign she gets more and more tired.

Relationship with the local community

Carolina tells me that during the work stay in Pakistan they are never alone, there are always local people from the village with them or in a house next door. They are always guarded for precautionary reasons, and are not allowed to go out anywhere on their own or to go sightseeing. Occasionally they receive an invitation to visit a bazaar or to go to university, but this is exceptional.

The work they do generates a lot of expectation among the local people, so it is often necessary to stop and interact with them. At first, this was confusing for Carolina, as in Europe we are not used to stopping while we work.

However, in Asia, hospitality is very important and the pace of life is very different, they don’t understand the rush we have in the West. Becoming familiar with their way of life and adapting to it is part of the job, as the work takes place in a different cultural context, and these are the things that enrich it the most.

Preserving endangered sites

In the Indus Valley there is a very high risk of sites disappearing for several reasons.

One of them is modern agriculture, the need to expand agricultural fields. Some sites are unknown or undocumented, popular knowledge of the residents of the area, and are therefore at risk of being destroyed. Protecting them is not easy, as they are located in areas of developing countries, so finding the balance between heritage conservation and maintaining agriculture as an engine of economic development is not easy.

In this regard, a current site detection project led by the University of Cambridge responds to this need (project called Mapping Archaeological Heritage in South Asia (MAHSA) in which ModAgrO is a partner), as do government agencies promoting the preservation, conservation and enhancement of heritage in the area.

On the other hand, there is a risk of sites disappearing due to erosion. Particularly in the dune areas of the desert, the movement of the sand and the action of the wind gradually erode and destroy them. For these reasons, the ModAgrO project is committed to carrying out a single campaign per site, with the intention of intervening and studying as many sites as possible before they disappear.

A day in the life of Carolina in Barcelona

What a day at work is like

It’s 7 am and Carolina’s alarm clock rings in Barcelona. Before having cereal or toast for breakfast, she takes the opportunity to do some housework (putting on the washing machine, cooking…). At around 9am she enters the university and, depending on the material she has available, she starts working on one thing or another.

Her daily work is carried out in 3 different spaces: laboratory, microscopy and magnifying glass room, and office. He works with two types of remains: macrobotanical remains (which do not need to be processed in the laboratory) and plant microremains (phytoliths and starches), which first need to be sampled and then processed in the laboratory.

The laboratory work consists of chemically removing the elements that are not of interest from these samples so that they are as clean as possible, following protocols according to each type of sample. Afterwards, the analysis of the micro remains is carried out with the microscope.

On the other hand, the macro remains (which can be seen with the naked eye), which do not need to be processed in the laboratory, are studied with a magnifying glass. These are those obtained from flotation, which are sieved by size and studied directly with the magnifying glass. Another part of the work is computer work in the office, such as polishing the data, writing an article, an abstract for a congress, etc.

Carolina takes a lunch break at 13h with the rest of the team. Each one brings a tupper, taking advantage of the fact that there is a kitchen and canteen at the University. This is a time to share things and find out about other colleagues’ work. Later, there is a coffee break – although Carolina doesn’t drink – accompanied by some sweets (there is always someone who brings something to share!). Then it’s back to work, more or less until 18h. Carolina tries not to take work home with her and makes the most of her free time, compensating for the mental work with exercise, dancing, creative activities… She has dinner around 10pm and takes the opportunity to read or watch a series before going to bed.

Sustainability and ecology: the case of millet

Archaeobotanical research helps to better understand the past, but also the present. One example is the case of millet. Millet is a very resistant cereal (to drought and to unfertile and unfavourable soils), with very short growth cycles.

It is now being discovered that it has traditionally been very important in the agriculture and cuisine of the Indus Valley communities, but has suffered a decline in use and social conception. Millets are known as «famine cereals», and are associated with animal feed. People want to eat wheat or rice, but these require a lot of water. At a time of aridification and climate change, millet could be a much more environmentally friendly and sustainable option, and just as nutritious.

Until now, it was not known to have occupied such an important place in ancient times because of the study techniques used. Millets are very small cereals, so in flotation it is much more likely to lose millet residues than wheat or barley. This leads to a bias, as it is easier for the other grain types to be preserved in the archaeological record. Nowadays, however, micro-study allows us to differentiate whether they are millets or not by means of micro-traces. The discourse that was known until now was that wheat and barley were consumed in the Indus River plain settlements, but we now know that millet consumption was much more important than previously reported. This leads us to consider socio-economic and cultural as well as environmental factors in explaining changes in cultivation and diet in the Indus Valley during prehistoric times.

Fortunately, 2023 was declared the International Year of Millet by the FAO, which has helped to share information about millet, including recipes on how to cook it!

You can download the manual here:

Ethical issues and science dissemination

In a research project involving several countries, one of the questions I was wondering about was how the collaboration is developed and what material stays in the country of origin, in this case Pakistan.

Carolina explained to me that there is a signed agreement (memorandum of understanding – MOU) in which everything is previously agreed upon by the parties involved. From Barcelona, for example, they only take care of the archaeobotanical part because they have the necessary facilities, materials, techniques and knowledge. On the other hand, other materials such as ceramics or terracotta figurines, which can be exhibited in museums, remain at the University of Pakistan, after having been documented and inventoried.

Currently, the Barcelona team wants to put more emphasis on dissemination. The aim is to bring heritage closer to society, so that knowledge does not remain just in a scientific journal. To this end, they hope to collaborate with the Pakistan team in improving the narrative of their museums, such as the National Museum of Pakistan in Karachi.

However, we cannot fail to mention the importance of the scientific documentation that emerges from this type of project. Here is an example of a scientific publication by Carolina and her colleague Jennifer Bates, so that you can see for yourselves the results of the great work we have discussed in this article:

Conclusion

First of all, I would like to thank Carolina for letting me accompany her in her day-to-day work. Seeing the hard work behind an archaeological research project gives a better understanding of the challenges that research teams face on a daily basis. On the other hand, it reaffirms the importance of the study of archaeological discoveries which, when put in relation to the workings of traditional modern societies – which is the responsibility of Ethnoarchaeology -, help us to better understand our own history.

I have been particularly struck by how some of the beliefs that were held in the past stemmed from a bias derived from the methods of scientific study, as well as the force that socio-cultural prejudices can exert on people’s habits and customs. Thus, through the ModAgrO project, we have seen how archaeological and palaeoenvironmental information allows us to better understand the behaviour of past societies and traditional knowledge, which sometimes endures and evolves to the present day.

Below is a short video in which you can listen to Carolina. I also highly recommend listening to the fantastic podcast (in Spanish) by National Geographic Spain and the Palarq Foundation on the secrets of the Indus Valley civilisation, which provides different and very interesting information on the subject.

Keen to learn more about cultural heritage conservation? Then check out the article on artefact restoration with restorer and artist Giorgia Cipollone and the article on archaeological conservation with Dr. Mònica López-Prat!

Pingback:RESTORATION OF CULTURAL ARTEFACTS - Alba Cid