On returning from Japan, it is easy to feel what Xavier Moret described in his book Historias de Japón (2021): «on the first trip, you feel capable of writing a book about the country; on the second, you realise that it is not easy to explain so much complexity in words, and finally, when you have been there a few times, you think it would be daring to attempt the first».

This is how I perceive this beautiful country: rich, complex and unfathomable as a foreigner.

Today I talk about cultural heritage and sustainable tourism in Japan. I first address the contrasts and manifestations of its culture, and then discuss its position in terms of sustainability with Benjamin Wong and Fumiko Yoshida, founders of Tricolage Inc.

Tricolage Inc. is the first Japanese tour operator to have received the GSTC tourism sustainability certification. Find out more about them at the end of the article!

Tokyo or listening to silence in the world’s most populous city

As soon as you land in Tokyo, you get a sense of what awaits you in Japan, a country of stimuli and contrasts. Tokyo is similar to other Asian cities in that it smells of soy sauce in the streets, as food is always present and available (surprising to a European unaccustomed to the abundance of street food). However, it immediately sets itself apart from all of them and exudes a unique essence.

Tokyo is a metaphor for a country that is clean and spotless without having a single litter bin on the streets, a country where you are able to hear silence in the most populous city in the world. This already tells us a lot about a society that shows above all politeness, respect and cordiality.

When you travel around Japan, differences between its people are immediately apparent. In Tokyo, we encountered a highly courteous and attentive treatment, while in Osaka the atmosphere was more relaxed. North of the island of Hokkaido, we found colder gestures and sometimes felt more like we were in Russia than in Japan (even by the language on the signs).

One example of the contrasts throughout the country is its trains. If you travel the country by train, you can catch everything from bullet trains to vintage trains that the driver has to stop manually when a deer crosses his path. High-tech meets tradition all over Japan.

Washi paper: Intangible Cultural Heritage

Traditional Japanese culture is fascinating and encompasses many representations that are still alive today. One of these manifestations is the traditionally made Washi paper, which was declared an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2014.

This paper is not only used in various traditional arts such as calligraphy (shodō) or origami, but also to make objects such as lanterns or the sliding doors of traditional houses, as it is very resistant. Even dresses have been made with it.

Those who read this blog know my passion for writing and art, and consequently for all the supports and materials related to them. It is for this reason that during my trip to Egypt I also became interested in the history of papyrus and the pictorial methods of tempera painting.

In Japan it could not be otherwise. In order to find out more about how this paper is made, I went to the Tokyo Ozu Washi shop and museum, which dates back to 1653, where I had booked an appointment for a workshop.

The «Handmade Washi Experience»

On my arrival, I was very kindly welcomed by Tanaka san, who was to be my teacher for the whole experience. First of all, she accompanied me to the gallery on the 2nd floor, a very interesting area for its display of items made with Washi paper. Here I was able to watch a 15-minute video on traditional papermaking, which allowed me to see stages of the process such as: cutting down the branches from the Kozo tree, steaming and peeling them, washing the inner layer of the bark, boiling it and removing impurities of each skin to obtain kozo fibers, and then beat them with a wooden hammer on a woodblock or on a stone board to separate them.

When we went to the studio, Tanaka san had everything ready to start the experience with quick-drying techniques. In this way we were able to make a plain Washi paper and a Rakusui paper. Making the paper oneself allows you to see how complicated and meticulous the handmade production of this paper is.

With this experience, the Ozu Washi shop spreads the importance of preserving this traditional method and allows us to see the transformation of the fibres into paper as if it were magic. After the workshop, I still had time to enjoy the historical museum on the 3rd floor and visit the shop.

The traditional craft of hand-making paper is practised in three communities throughout Japan: Misumi-cho in Hamada City (Shimane Prefecture), Mino City in Gifu Prefecture and Ogawa Town/Higashi-chichibu Village in Saitama Prefecture. If you are interested in discovering the roots of their making, one way to engage in sustainable tourism in Japan by sharing and promoting their cultural heritage is to participate in the activities they offer.

A book district in tokyo

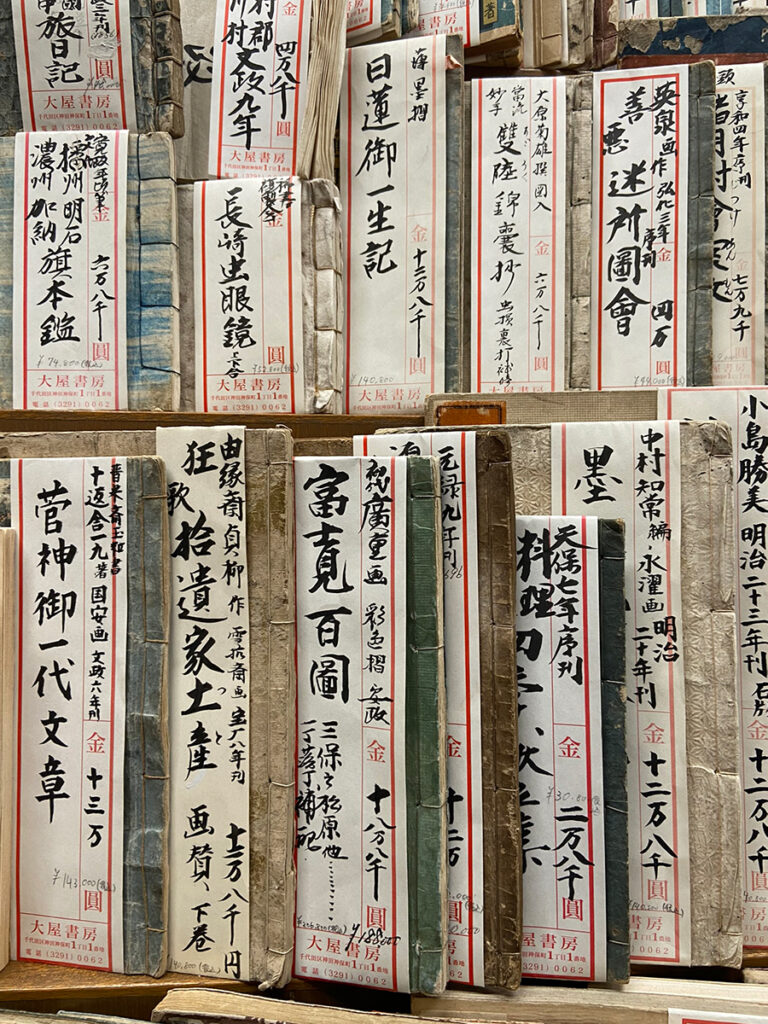

To round off the experience, I headed to Tokyo’s bookstore district: Jinbocho. Unlike other better-known areas, such as the otaku district of Akihabara or the Shibuya crossing, the Jinbocho district is more hidden from tourists. Here you will find a concentration of bookshops, including small antiquarian bookshops, where you can find precious objects from the world of books, calligraphy and art.

There are also several shops in Tokyo where you can buy materials for shodō, such as Kyukyodo in the Ginza district, or simply huge stationery shops such as Itoya, with 12 floors of office and art supplies.

Overtourism in Kyoto – problems of sustainable tourism in Japan

As early as 1993, Alex Kerr pointed out in his book Lost Japan that Kyoto is a «fragile city», «in danger of extinction», and it is true that it is one of the cities that has suffered most from tourist overcrowding. Just walking around Kyoto, the presence of Western tourists is immediately noticeable.

In Kyoto, many traditional houses have been destroyed to create hotels or tourist flats. Despite the fact that some temples and historic buildings are protected, walking through the city today you can see that there is little left of the traditional city. Unfortunately, this phenomenon is now slowly also affecting the town of Takayama in the Japanese Alps.

Kyoto is home to two of the most visited places in Japan: the Arashiyama bamboo forest and the Fushimi Inari temple with its 1000 torii gates. While these are both undeniably impressive places, neither the modern traveller nor the locals who want to visit the temple and the forest are able to have a quality experience.

I have witnessed in winter how both places suffer from the negative consequences of overtourism and «selfie tourism», and I can imagine that during the cherry blossom (sakura) or summer season it is much worse.

In 2021 I was delighted to see Kyoto in the Green Destinations organisation’s Top 100 Destination Sustainability Stories selection. It showed how local tourism companies had collaborated with health institutions to develop a strategy to restore tourism after the pandemic by avoiding overtourism. However, it is evident in 2023 that the measures taken are still insufficient.

Northeast Hokkaido

The contrast between Kyoto and the north-east of Hokkaido Island in winter is so strong that it seems as if they are different countries. This area is a paradise for nature and wildlife lovers. The setting is spectacular and the snowy landscape, with the frozen ocean in Nemuro Bay, is breathtaking.

However, this area is difficult to reach, and the shortage of Western tourists soon becomes apparent. We moved from the island of Honshu, where the major cities are perfectly connected by bullet trains (shinkansen) that tourists can use with the JR Pass, to the island of Hokkaido, where the outlying areas can become a nightmare on public transport.

Arriving in Kushiro, if you want to visit the Tsurui Ito Tancho Crane Sanctuary, one of the area’s attractions along with Lake Toro and Shitsugen National Park, you’ll have a hard time using public transport. When one is committed to sustainable tourism, one way to contribute favourably is to use public transport.

If you arrive via the airport, it takes about 2 hours to make a 40-minute drive, at a time of year when it gets dark around 4-5pm. Arriving at the sanctuary, one quickly notices that most of the tourists there, mainly wildlife photographers with their tripods set up, travel with their own vehicles to easily access the different sites in the area.

Even further east

The same applies to Nemuro. Nemuro is 120km from Kushiro (3 hours by JR train) heading towards the easternmost point of Hokkaido (Cape Nosappu). The surrounding area is home to the stunning Furen Lake, Nemuro Bay to the north of the Nemuro Peninsula and the Pacific Ocean to the south. Arriving at the train station, information leaflets with a recommended bird-watching itinerary read: «meet a bird-watching guide or rent a car». It quickly becomes clear that the public transport option is not suitable.

If you persist with the idea, the result is that you are drastically limited in the places you have time to visit, as the buses run infrequently and the schedules are inconvenient. For example, there are only 3 buses running on weekdays from Nemuro station to Lake Furen, and on weekends there are only 2. Once again, we noticed that photographers who travel around the area in search of wildlife have a personal van to travel around in.

On the train ride back to Tokyo (a very long journey of 5 trains), more western tourists start to show up as we approach Sapporo and Hakodate: clearly the city and ski areas are more accessible, require less effort and are more attractive.

A coffee around sustainable tourism in Japan

I began this article by saying that Japan feels somewhat inaccessible as a tourist. The barrier that separates you from the locals is palpable, largely imposed by the language gap. It was Benjamin who told me that in Japan 99% of the resident population is Japanese, a fact that helps to understand many of the traveller’s perceptions during their trip.

Benjamin Wong is the co-founder, together with Fumiko Yoshida, of the Tricolage agency, the first Japanese tour operator to receive the GSTC (Global Sustainable Tourism Council) certification for its commitment to sustainable tourism. Having coffee with Benjamin and Fumiko was great news and something I had been looking forward to. I had many questions to ask them about their adventure as entrepreneurs and ambassadors of sustainable tourism in Japan.

Sustainable tourism in Japan: unique travel experiences

The first thing that strucked me during our conversation was the passion and commitment of both of them. Deciding to launch a tourism initiative in the middle of a pandemic shows boldness and conviction, and this is how Tricolage was born in 2020.

Since then, they have been crafting sustainable journeys for high-end travellers and providing consulting services on sustainability for companies and organizations. The start was not easy, they tell me, both because of the context of the health crisis and because they were in a country that is not yet firmly committed to sustainable tourism.

Crafting bespoke journeys

Tricolage designs tailor-made and sustainable journeys for travellers. Thanks to their experience, they know and understand the needs of international tourists. The itineraries are tailor-made according to the travellers’ preferences. To do this, they personally visit the destinations they offer and learn first-hand about the experiences they propose. They work with local partners and promote the local economy.

The local culture and traditions of the country are very present in all Tricolage’s proposals. I mentioned earlier in this article that accessing Japanese culture as a foreigner is very difficult, but Tricolage’s tailor-made trips help to overcome this obstacle. They bring you closer to the artisans’ work and allow you to get to know their experience first hand. All this with the utmost respect and care for these traditions, without turning them into a mere tourist attraction.

Sustainable Luxury

One of the questions I had for Tricolage was about their «Sustainable Luxury» approach, I wanted to know more about it. First, they explained to me that they conceive of sustainability as the new luxury.

Traditionally luxury has been associated with excess and individualism, however, sustainability (which is essentially «meeting the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs») can go hand in hand with luxury. For Tricolage, modern luxury in travel is synonymous with wellbeing, self-care and quality experiences that are appreciated with respect and responsibility.

Afterwards, Fumiko explained to me concretely that in order to promote local economic sustainability and to pay their suppliers fairly, they couldn’t offer very low prices.

Likewise, she told me about how in Japan are high-end hotels currently the ones that are responding most favourably to an ecological transition and the search for truly sustainable answers that go beyond the elimination of plastics.

Certainly, a supply chain transformation is needed first in order to offer a more sustainable travel experience.

The great success of Tricolage so far is that it is making sustainable tourism in Japan available, conscious and credible.

Concluding a trip to Japan

After my trip through the land of the rising sun, seeing how this beautiful and rich country suffers in many places from tourist overcrowding, I am happy to conclude with my meeting with Benjamin and Fumiko, who despite the difficulties stay on it, providing sustainable solutions and advocating for sustainability in Japan.

If you want to know more about traditional culture and sustainable tourism, follow the latest news on Instagram!